The checks that determine whether we are docking... or just crashing

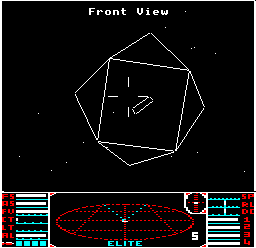

Docking is difficult, there's no doubt about it. The challenge of slotting into one of Elite's rotating Coriolis space stations is absolutely iconic, and for almost everyone, the first few attempts to match the station's rotation while heading into the middle of the slot end in messy failure. It is one of the biggest hurdles to overcome in the early game, but to progress you have to master the art to the point where it's almost a shame when you can afford a docking computer to handle things for you. Almost.

But how does the game know when we successfully snake into the docking bay, rather than crashing into the station walls, leaving nothing but a trail of sparks and dented pride? The routine at ISDK in part 9 of the main flight loop houses the heart of the docking algorithm, which watches us nervously line up with the planet-facing side of the station, and judges whether our approach is nominal or abominable. It's called from

Specifically, the ISDK routine does five tests to confirm whether we are docking safely. They are:

- Friend or foe: Confirm that the station isn't hostile, because stations have feelings too - feelings and whole nests of Vipers

- Orientation: Confirm that our ship is pointing in the right direction, by checking that the angle that we are facing is within 26° of the perfect, head-on approach

- Heading: Confirm that we are facing towards the space station

- Location: Confirm that we are within a small "cone" of safe approach

- Rotation: Confirm that the slot is less than 33.6° off the horizontal

Here's a further look at how these tests work.

1. Check how friendly the station is

------------------------------------

This is the easiest check to do. The station is hostile if bit 7 of byte #32 of the station's ship data is set, so all we do is fetch that byte and check to see of it is negative. If it is, then the station is hostile, so docking ends badly.

2. Check the angle of approach

------------------------------

The space station's ship data is in INWK. The nosev vector in byte #9 to byte #14 is the station's forward-facing normal vector, and it's perpendicular to the face containing the slot, pointing straight out into space out of the docking slot. You can see this in the diagram on the left, which is a side-on view of the station, with us approaching at a jaunty angle from the top-right, with the docking slot on the top face of the station. You can imagine this vector as a big stick, sticking out of the slot.

nosev

^ ship

: /

: /

: L

: /

: t / <--- approach

: / vector

: /

:/

____====____

/ /\ \

| / \ |

| / \ |

: . station . :

We want to check whether the angle t is too large, because if it is, we are coming in at the wrong angle and will probably bounce off the front of the space station. To find out the value of t, we need to look at the geometry of this situation.

The station's nose vector has length 1, because it's a unit vector. We actually store a 1 in a unit vector as &6000, because this means we don't have to deal with fractions. We can also just consider the high byte of this figure, so 1 has a high byte of 96 when we're talking about vectors like the station's nose vector.

So the nose vector is a big stick, poking out of the slot, with a length of 1 unit (stored as a high byte of 96 internally).

Now, if that vector was coming perpendicularly out of the screen towards us, we would be on a perfect approach angle, the stick would be poking in our face, and the length of the stick in our direction would be the full length of 1, or 96. However, if our angle of approach is off by a bit, then the nose vector won't be pointing straight at us, and the end of the stick will be further away from us - less "in our face", if you like.

In other words, the end of the stick is less in our direction, or to put it yet another way, it's not so far towards us along the z-axis, which goes in and out of the screen.

Or, to put it mathematically, the z-coordinate of the end of the stick, or nosev_z, is smaller when our approach angle is off. The docking routine uses this method to see how well we are approaching the slot, by comparing nosev_z with 214, so what does that mean?

We can draw a triangle showing this whole stick-slot situation, like this. The left triangle is from the diagram above, while the triangle on the right is the same triangle, rotated slightly to the left:

^ ship ________ ship

: / \ |

: / \ |

: L \ v

: / 1 \ | nosev_z

: t / \ t |

: / \ |

: / \ |

:/ \|

+ station + station

The stick is the left edge of each triangle, poking out of the slot at the bottom, and the ship is at the top, looking down towards the slot. We know that the right-hand edge of the triangle - the adjacent side - has length nosev_z, while the hypotenuse is the length of the space station's vector, 1 (stored as 96). So we can do some trigonometry, like this, if we just consider the high bytes of our vectors:

cos(t) = adjacent / hypotenuse

= nosev_z_hi / 96

so:

nosev_z_hi = 96 * cos(t)

We need our approach angle to be off by less than 26°, so this becomes the following, if we round down the result to an integer:

nosev_z_hi = 96 * cos(26)

= 86

So, we get this:

The angle of approach is less than 26° if nosev_z_hi >= 86

There is one final twist, however, because we are approaching the slot head on, the z-axis from our perspective points into the screen, so that means the station's nose vector is coming out of the screen towards us, so it has a negative z-coordinate. So the station's nose vector in this case is actually in the reverse direction, so we need to reverse the check and set the sign bit, to this. Setting bit 7 of 86 gives us 214, so we get this:

The angle of approach is less than 26° if nosev_z_hi <= 214

And that's the check we make in ISDK to make sure our docking angle is correct.

3. Heading in the right direction

---------------------------------

Before we can work out whether we are facing towards the space station, we need to get the vector from us to the space station. Once this is done, it's an easy check to see whether the sign of the z-coordinate of that vector is positive or negative. Negative means the space station is behind us, so if that's the case, we're falling into the station backwards, which doesn't end well.

4. Cone of safe approach

------------------------

This is similar to the angle-of-approach check, but where check 2 only looked at the orientation of our ship, this check makes sure we are in the right place in space. That place is within a cone that extends out from the slot and into space, and we can check where we are in that cone by checking the angle of the vector between our position and the space station.

The check is whether the z-coordinate of the vector is less than 89, in which case we fail to dock. The z-coordinate of the vector between our ship and the centre of the station uses 96 to represent the unit vector length, so we can use the same cosine calculation as step 2 to calculate the cone's angle at the largest permissible value of 89:

cos(t) = 89 / 96

which gives an angle of t = 22.0°. So if we approach the slot outside of a 22° cone of approach, where the cone extends from the centre of the station, then we will fail to dock successfully.

5. Horizontal docking slot

--------------------------

The space station is one of the ships with a non-standard orientation (see the deep dive on orientation vectors for details). Specifically, the roofv vector points out of the side of the space station in a direction that is parallel to the horizontal line of the slot.

As we are approaching the station and trying to dock, then, the roof vector is pointing to the side when the slot is nice and horizontal. If we start to veer away from the horizontal, the roof vector will start to tilt further up or down, so instead of pointing to 3 o'clock or 9 o'clock, it will tilt above or below.

As the vector tilts away from the horizontal, its x-coordinate component will start to shrink, as the x-axis goes from right to left. So this test:

|roofv_x_hi| >= 80

makes sure that the slot is reasonably horizontal. Specifically, the maximum angle we are allowed to be off the horizontal by is given by:

cos(t) = 80 / 96

which gives an angle of t = 33.6°. So if we approach with the slot at an angle of more than 33.6°, we will fail to dock successfully.